The impact of COVID-19 on South Africa's economy

By Jason Muyumba, Charlotte Mateya, Sisipho Toto and Tshegofatso Bogatsu

South Africa has a reputation that far precedes it, known as the world’s biggest gold and platinum producer and the leading producers of metals and coals. It’s a country with a rich and diverse history, and understandably so, a diverse foundation of global investors. Recently, South Africa’s economy was dealt a hard blow when our credit rating, a critical indicator for global investors, was downgraded to BB+ also known as ‘junk status’ by Moody’s. The risk of South African debt has increased and the health crisis, COVID-19, has made it worse. The purpose of this post is to highlight the challenges South Africa is faced in the age of COVID-19, how these impact the economy and what needs to be addressed to ensure the survival of the country and maintain interest from global investors.

State of the Economy before COVID-19

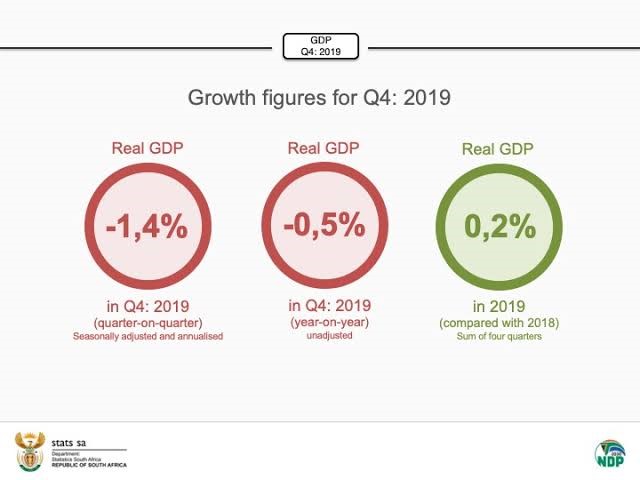

South Africa is a country on the Southern tip of the African continent. It is known to have advanced technological infrastructure and considered a developing economy. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Producer Product Index (PPI) and the unemployment rate are measures that show where the economy of the country is at a particular time. GDP measures the value of economic activity within a country. According to data from Stats SA, Real GDP (which measures a country’s growth in real terms – accounting for inflation) decreased by – 1.4% in the fourth quarter of 2019, following an increase of 0.8% in the last quarter of 2018. It has been projected to rise to 1.1% in 2020. South Africa has been on the looming lines of a recession for the past two years but has managed to avoid it in 2019 and early 2020 before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was largely due to the significant drags in the transport and trade sectors’ contributions to GDP. While the finance, real estate and business services sectors together contributed 2.7% growth, alongside the mining sector’s 1.7% growth. PPI is the measure of the change in the prices of goods as they leave their place of production or enter production processes (StatsSA, 2020). The headline PPI inflation, in the country, stood at 4.6% in January, followed by a decrease to 4.5% in February. This was due to petroleum, chemical, rubber and plastic products increasing by 6.8% year-on-year and contributing 1.4% points, indicating a strong growth in prices in the industries producing or using these commodities and goods in their production process.

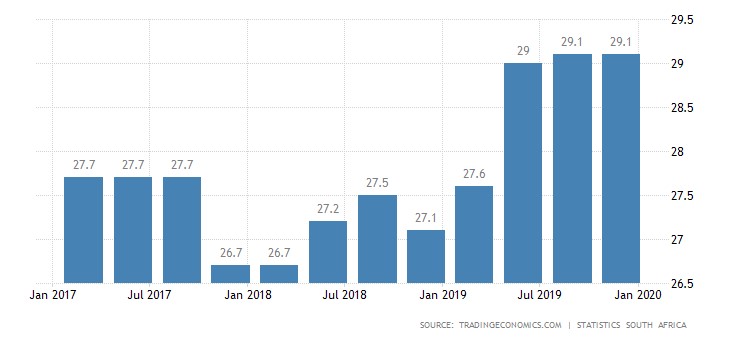

The unemployment rate, which measures the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the labour force, stood at 29.1%, meaning we observed a marginal decrease at the beginning of this year where it stood at 29,0% (StatsSA, 2020). There is not much of a difference in the unemployment rate. The slight difference is due to job creation in the business services and community services industries which added 12 000 and 3000 jobs, respectively. As we have observed, the changes in the GDP, PPI and unemployment rate in the economy were reasonably stable with different sectors working relentlessly to contribute to the overall growth of the economy.

The Impact of COVID-19 on South Africa’s Labour Market

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of society and human life. Yet few structures of society have felt the impact of the pandemic as hard as the labour market. This paints a chilling picture for South Africa’s historically volatile and ailing labour market that has largely failed to meet the needs of citizens. It is well known that the labour market has struggled with structural unemployment, inflexible labour regulations and high labour costs for several years (Dadam, 2017).

To expand on the point made above in relation to unemployment, there are two metrics we can use to account for unemployment in the economy. These are known as the narrow definition of unemployment (measures unemployment as the percentage of labour market participants – active job seekers and employed labour – without jobs) and the expanded definition of unemployment (measures unemployment as the percentage of the working age population without employment). Based on 2019 Q:4 data, the narrow measure sits at 29.1%, while the expanded comes in at 38.7% (Trading Economics, 2019). This is the highest level of unemployment that the country has recorded in its democratic dispensation. It is worth mentioning that the largest contributors to the spike in unemployment were caused by job losses in the manufacturing, trade and utilities sectors in response to the ongoing power crisis at Eskom. The majority of jobs are formal in nature and are in the manufacturing, trade, business services and community services industries (StatsSA, 2020). Furthermore, an article by The Conversation (2019) states that the informal sector is believed to employ approximately 20% of the labour market, based on StatsSA’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS). It is with this insight in mind that we can assess the potential impact of COVID-19 on the labour market in South Africa.

The Impact on Trade

International trade is one of the most important discussions taking place not only in South Africa but globally on a daily basis. Countries depend on each other to survive, to this end, countries trade with one another when they do not have resources to satisfy their own needs and wants. The President of South Africa announced the national lockdown on March 26th 2020, with the aim of slowing down the rate of COVID-19 infections. This will inevitably cause major damage to the financial market and the larger economy. These restrictions make it almost impossible for trade to happen and businesses that generate their income from trade will expectedly buckle under the restrictions. Many industries rely on imports from a supply chain, typically with a large footprint in China.

Located on the border of the Yangtze River is Wuhan, the source of the COVID-19 outbreak. Wuhan is a significant and major transport hub, and also the capital of Hubei province. Hubei has more than 6000 foreign-invested companies that are from more than 80 countries, and the region produces 4.5% of China’s GDP. China is South Africa’s biggest supplier of imports and exports. Therefore, South Africa is still to face major economic uncertainty as a result of the outbreak. Cell phones, steel and iron, for example are South Africa’s biggest imports from China. The COVID-19 pandemic is a health crisis that could pose a serious risk to the economy through the standstill of production, restrictions of people’s movements and the cut-off of the supply chain. At large COVID-19 has caused a slowdown in global trade, has disrupted the global logistic networks, and changed tourism flows.

State of the Economy in the Wake of COVID-19

The outbreak of COVID-19 has unimaginably hit the economy of many countries – South Africa being no exception. Post the outbreak of the pandemic in South Africa and Moody’s downgrading of the country’s economy to junk status, the South African government will face higher debt servicing costs and that it will have to cut its spending as it becomes more expensive to borrow. Economist Duma Quabule stated that the 21 days lockdown has resulted in two thirds of the South African GDP being offline, that is between R6 billion to R8 Billion being taken out of the economy quarterly (Carte Blanche, 2020). This has left many trembling in fear of losing their jobs and not being able to not only provide for themselves but for their families. Businesses are fearing having to close down due to reserves running out and not having enough cash flow to cover their operational expenses as well salaries and wages of their employees.

Points of consideration:

- Non-essential businesses should be allowed to remain open. However, we are of the view that this should take place under a controlled environment that ensures the safety of employees and consumers. Where possible businesses should require the use of PPE for all employees. Screening processes should also be considered to monitor high-risk carriers. Places of high instances of public gathering should have clearly demarcated standing and sitting zones, as well as limited numbers of people in one place at a time. This will ensure that the widespread fallout for businesses is limited.

- We note with appreciation the move by the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) to reduce the repo-rate by 100 basis points (1%). This will stimulate deflated consumer spending and confidence, as well as encourage credit expansion for businesses in response to lowered bank interests. It is our view that the SARB considers an additional cut in interest rates in order to cushion the impact of the lockdown and pandemic amidst global speculation of an imminent recession.

- The should be an attempt by government to engage in the market by encouraging competition among businesses through the implementation of various strategies such as subsidies and tax reductions. This will ensure that consumers continue to benefit from low and fair prices, without which the issue of price hikes may arise under our present circumstances.

- The government should work with SMMEs to build investor confidence in the country, through displaying the same sense of coordinated effort to address social challenges as that exemplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The potential of the agricultural sector to, in part, address the eradication of poverty and equitable distribution of income must be embraced. Poverty will potentially reduce in poor communities owing to the labour that will be needed, which in turn will reduce unemployment, leading to economic growth in South Africa.

- Coming out of the pandemic, there is a need to invest in greater education and skills development that is technologically biased and relevant to the necessary skills of the future. While fast-tracking growth through investment in high potential sectors.

- Prioritise the provision of critical products and services, as well as its supplies by subsidising production and introducing a temporary export ban on critical goods, until there can be an assessment of potential shortages that may arise locally over the short-to-medium term.

Jason, Charlotte, Sisipho and Tshegofatso are currently pursuing Bachelor degrees in Commerce and Accounting.

Sharing is caring!

Help us spread the word about Voices Unite:

Such a compiled and convincing report of economic analysis it definitely made a difference